Some people compulsively shop for stationary and pens. Other people peruse, as they pass, shoe departments or bag displays.

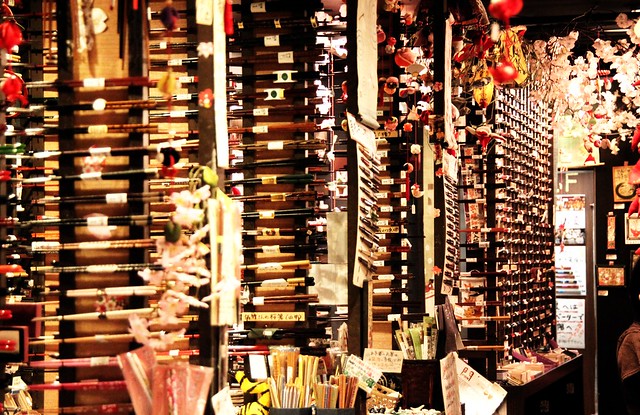

And others make it a point to find obscure, little chopstick stores and touch all of the pairs of artisan hashi (箸, はし) on display: hand-crafted of sacred woods from the deepest, oldest forests in Fukui, by artisans who have been spiral-filing by feel in Kyoto for more than four centuries.

When I saw my first 箸屋さん, I was filled with curiosity. When I saw my first pair of ¥$150 chopsticks, I was filled with incredulity.

Who would buy such a thing? And how many of those “whos” need to buy such such-a-things to maintain so many stores?

But, oh, what beautiful such-a-things they were.

Bamboo, maple, oak, composite. Round-cut, triangular, heptagonal, dodecahedral. Unmatched, interlocking fit, magnetic, lacquered, inlaid, embossed. All in patterns, shapes and designs befitting any kind of hand, any kind of personality.

It is quite common in Japan for people to have their own every-day place settings for meals. I have been to dinners where everyone has their own particular bowls, cups and plates, let alone their personal set of hashi. Even I have begun to use the same bowl and hashi out of habit.

Granted there are only two or three sets for me to choose from.

Then again, it’s not like people have houseguests over very much, so expansive matching sets of china aren’t particularly necessary. After all, where would I keep all of that extra flatware?

Dinner parties tend to be a hodgepodge of mismatched plates and bowls collected over the years

1The first pieces tend to be those that you inherit.

1, with personal pieces added through traveling or spontaneous investment.As such, when a couple gets married, it’s not uncommon for the bride and groom to receive new place settings, including “their own hashi,” as a symbolic cornerstone of their new home together.

Until then, dinner guests use whatever’s around. And that is most often 割り箸.

In the decades following the the breaking of the Sakoku (鎖国) by the West, Japan’s economy found itself under the dark shadow of the sails of Commodore Perry’s Black Ships. Disgruntled as opportunities at home stifled and sputtered under treaties signed with force of coercion and duress, by the middle of the 19th century, Japan began preparing to go to war in the hopes that they too may benefit from the Imperial Spirit of the age, seeking to find fortune and respect abroad, in an attempt to re-exert their own will over their economic future.

A major part of any war effort requires the redistribution and rationing of resources, especially light woods that would be used in the construction of ships and airplanes. This greatly depressed many domestic markets, including chopstick manufacturing, sweeping away base-supplies in support of the war.

As access to natural woods dried up, the Meiji-led government began encouraging manufacturers look towards re-appropriating discarded furniture, wood that could easily and cheaply be ground down and pressed into things like hashi that would remain constituted long enough for at least one meal and then could just as easily be discarded.

And, thusly, the disposable chopstick industry was born.

In 2011, Rachel Nuwer of The New York Times reported that in order to access the 3.8 million trees needed to supply the annual demand for the 57 billion pairs of disposable chopsticks, China would seek to unsustainably deforest 10,800 square miles of forest. A year.

That’s 6,912,000 acres.

To put that into context, Disneyland Park in Anaheim comes in at a whopping 85 acres. The whole of Disneyland Resort is reportedly 500 acres. Of that, the seemingly massive Mickey and Friends Parking Lot is a mere 100-acres of stacked space. Disney World and its 36 on-site hotels, four theme parks, two water parks, four golf courses, camping resort and residential area, comes in at only 30,080 acres.

In fact, all 6 resorts combined

2Which would include the soon-to-be-opened-in-2016 Shanghai Disney Resort

2 logs in at a massive 36,918 acres.It would take a space equivalent of 230 Disney Worlds a year to grow enough trees to produce the 57 billion pairs of chopsticks needed in 2011.

Of those 57 billion pairs of chopsticks, around a half are used domestically in China, while the remaining half are distributed to Japan, South Korea and the United States.

Unsurprisingly, Japan receives a majority of the remainder, at 77% of that 50% (making for 38.5%). Or using the numbers Nuwer offered previously, Japan consumes 22 billion pairs of China’s disposable chopsticks

3Called waribashi (割り箸, わりばし) in Japan.

3, making them accountable for almost 1.5 million of those trees in China. A year.Of course, that was back in 2011.

In Jiro Taylor, using a bit of magic and an incredible list of un-cited sources, claims that with 24 billion pairs of waribashi washing ashore, Japan’s annual consumption of disposable chopsticks has reached 185-pairs per person.

And while I have no stats to back that up, I can confess that this number may be about half of my own annual usage.

None of which has or ever will be recycled.

Unlike the absurdity that is plastic packing (re-packing and re-re-packing) in Japan, there is no “hashi-friendly” trash bag for disposable chopsticks. Soiled is the common term for used chopsticks. And, as with all soiled potentially-recyclable materials, after one use, it goes into the 燃えるゴミ bin without nary a concern.

And while convenience stores have begun asking 「箸をお使いになりますか?」mere picoseconds before dumping a handful of disposables into your bag out of habit, there is hardly a circumstance where someone says “no."

The recommended supply-side solution is the purchase of what have come to be called “マイ箸” (“My Hashi”): sturdy, no-nonsense, reusable chopsticks that you carry around with you.

I have a pair that find their home in the desk-drawer in my office. And while they certainly get used in place of waribashi for the days I happen to eat lunch at my desk, I never whip them out at restaurants. Or, really, otherwise.

Occasionally, I still find myself in a Hashi-Gallery when I’m out and about

4Unlike 手拭い (てぬぐい, tenugui), I have yet to plan trips specifically around hashi-shopping. Yet.

4. Actually, there are still one or two hashi places I take guests to when we happen upon 表参道 or 谷中銀座. I like to imagine that these storefronts are looking glasses, bridges to the ancient Floating Worlds of Edo and Kyoto.That and who doesn’t secretly want their own personal pair of hand-crafted chopsticks, selected from the rack only after deep reflection with no less solemnity than could be afforded of a wizarding wand. Of the hundreds there, to find a hashi that speaks to you; linking you to places both mystical and temporal, costly and ever-present.

Who doesn’t want that?